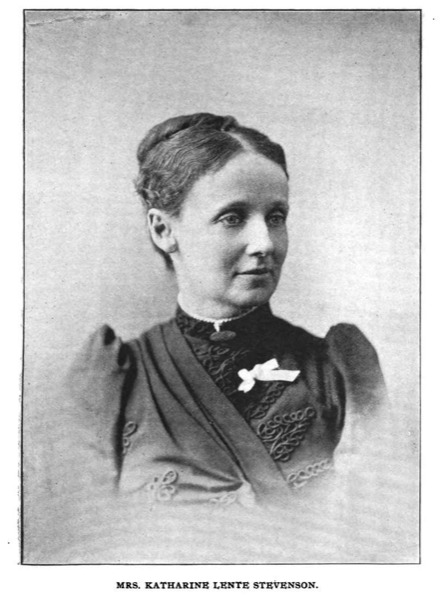

Katharine Lent Stevenson

Namesake of the Katharine Lent Stevenson Memorial Fund

Dublin Core

Title

Katharine Lent Stevenson

Namesake of the Katharine Lent Stevenson Memorial Fund

Namesake of the Katharine Lent Stevenson Memorial Fund

Description

Katharine Lent (sometimes spelled Lente) was born in Copake, New York in 1853 to Marvin Richardson Lent, a Methodist minister, and Hannah (Louzada) Lent. She attended Amenia Seminary in New York, graduating as valedictorian in 1875. She went on to earn a degree from Boston University’s School of Theology in 1881, where she was the only woman in her class. Lent married James Stevenson, a Boston merchant, around 1882, and became stepmother to his three young daughters.

Katharine had been involved in the temperance movement since the age of fourteen, when she had joined the International Order of Good Templars in New York. She became a member of the Allston-Brighton branch of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in 1887, when she was serving as an associate pastor at the Allston Methodist Episcopal Church. The position was short-lived, as Stevenson was terminated after the General Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church refused to recognize women as preachers, but her WCTU connections offered her new opportunities. She was appointed the Suffolk County Superintendent of Evangelistic Work for the WCTU around 1887, and then elected Corresponding Secretary of the Massachusetts WCTU in 1891. Her devotion to the cause earned her a position as Corresponding Secretary of the National WCTU in 1893, an office she occupied for five years.

Soon after her election to the National WCTU, Stevenson took on another role in the temperance movement, moving briefly to Chicago to work as an editor in the Department of Books and Leaflets at the Woman’s Temperance Publishing Association. During this time, she also published her book A Brief History of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (1907), and served as a contributing editor to the WCTU periodical the Union Signal, writing frequent articles about women’s rights and social reform. Stevenson returned to Boston in 1898 to accept a position as President of the Massachusetts WCTU, serving for the next twenty years.

While working for the Massachusetts WCTU, Stevenson also became active in the World’s WCTU, serving as Superintendent of its Promotion of Good Citizenship Department between 1907 and 1910 and overseeing its World Missionary Fund until 1913. In 1908, she took a leave of absence from her Massachusetts WCTU work so she could travel the world as a temperance missionary, visiting schools and churches in Hawaii, China, New Zealand, and India, among other places. She spoke about her experiences in a Boston Globe interview in 1910, condemning the “influence of western civilization in spreading the drink and cigarette habits” to other countries.

At home as well as abroad, Stevenson was a staunch Prohibitionist, often writing in support of a federal Prohibition amendment and attending hearings on temperance legislation at the Massachusetts State House. For Stevenson, a member of the Massachusetts Equal Suffrage League, the temperance cause was inextricably linked to the struggle for women’s voting rights. In 1914, Stevenson penned an essay arguing that corrupt politicians associated with the liquor trade knew that “with universal woman suffrage the doom of the organized, legalized, liquor traffic is sealed,” and therefore continued to deny women the vote in an effort to maintain their own power.

In 1918, Stevenson retired as President of the Massachusetts WCTU and returned to the National WCTU, where she became Superintendent of Americanization. She held this position until March of 1919, when she died suddenly while on a trip to Des Moines, Iowa. Shortly after her death, her colleagues at the Massachusetts WCTU established the Katharine Lent Stevenson Memorial Fund at Simmons in her honor, citing the College’s vocational mission as one Stevenson would have admired. They asked each WCTU member to donate twenty cents to the fund, one for each year of Stevenson’s term as President.

Katharine had been involved in the temperance movement since the age of fourteen, when she had joined the International Order of Good Templars in New York. She became a member of the Allston-Brighton branch of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in 1887, when she was serving as an associate pastor at the Allston Methodist Episcopal Church. The position was short-lived, as Stevenson was terminated after the General Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church refused to recognize women as preachers, but her WCTU connections offered her new opportunities. She was appointed the Suffolk County Superintendent of Evangelistic Work for the WCTU around 1887, and then elected Corresponding Secretary of the Massachusetts WCTU in 1891. Her devotion to the cause earned her a position as Corresponding Secretary of the National WCTU in 1893, an office she occupied for five years.

Soon after her election to the National WCTU, Stevenson took on another role in the temperance movement, moving briefly to Chicago to work as an editor in the Department of Books and Leaflets at the Woman’s Temperance Publishing Association. During this time, she also published her book A Brief History of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (1907), and served as a contributing editor to the WCTU periodical the Union Signal, writing frequent articles about women’s rights and social reform. Stevenson returned to Boston in 1898 to accept a position as President of the Massachusetts WCTU, serving for the next twenty years.

While working for the Massachusetts WCTU, Stevenson also became active in the World’s WCTU, serving as Superintendent of its Promotion of Good Citizenship Department between 1907 and 1910 and overseeing its World Missionary Fund until 1913. In 1908, she took a leave of absence from her Massachusetts WCTU work so she could travel the world as a temperance missionary, visiting schools and churches in Hawaii, China, New Zealand, and India, among other places. She spoke about her experiences in a Boston Globe interview in 1910, condemning the “influence of western civilization in spreading the drink and cigarette habits” to other countries.

At home as well as abroad, Stevenson was a staunch Prohibitionist, often writing in support of a federal Prohibition amendment and attending hearings on temperance legislation at the Massachusetts State House. For Stevenson, a member of the Massachusetts Equal Suffrage League, the temperance cause was inextricably linked to the struggle for women’s voting rights. In 1914, Stevenson penned an essay arguing that corrupt politicians associated with the liquor trade knew that “with universal woman suffrage the doom of the organized, legalized, liquor traffic is sealed,” and therefore continued to deny women the vote in an effort to maintain their own power.

In 1918, Stevenson retired as President of the Massachusetts WCTU and returned to the National WCTU, where she became Superintendent of Americanization. She held this position until March of 1919, when she died suddenly while on a trip to Des Moines, Iowa. Shortly after her death, her colleagues at the Massachusetts WCTU established the Katharine Lent Stevenson Memorial Fund at Simmons in her honor, citing the College’s vocational mission as one Stevenson would have admired. They asked each WCTU member to donate twenty cents to the fund, one for each year of Stevenson’s term as President.

Source

Internet Archive

Citation

“Katharine Lent Stevenson

Namesake of the Katharine Lent Stevenson Memorial Fund,” Suffrage at Simmons, accessed March 10, 2026, https://beatleyweb.simmons.edu/suffrage/items/show/92.

Namesake of the Katharine Lent Stevenson Memorial Fund,” Suffrage at Simmons, accessed March 10, 2026, https://beatleyweb.simmons.edu/suffrage/items/show/92.