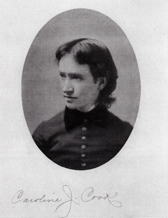

Caroline J. Cook

Faculty, Business and Law

Dublin Core

Title

Caroline J. Cook

Faculty, Business and Law

Faculty, Business and Law

Description

Caroline Jewell Cook was born in Evansville, Indiana in 1863 to Henry and Caroline (Judson) Cook. She earned an A.B. from Wellesley College in 1884 and later attended the Boston University School of Law, graduating in 1899. The following year, she applied to Harvard Law School, a common practice at the time for recent law graduates who wished to obtain a higher status degree. Though Harvard University had recently adopted a new merit-based admissions system, women applicants seldom received equal consideration, and Cook’s application was rejected; Harvard Law School would not admit its first female students until 1950. Nevertheless, Cook was admitted to the Massachusetts and Indiana Bar Associations in 1900, becoming the first woman to be bar certified in two different states.

Cook began her teaching career while still in law school, teaching Latin at the Dana Hall School in Wellesley between 1891 and 1899. After passing her bar examinations, Cook went into private practice, maintaining a law office on Beacon Street in Boston, but she never entirely gave up teaching. She taught courses in Business Methods and Commercial Law at Simmons in 1907 and again from 1910-1913, and also returned intermittently to Wellesley during this time as an instructor in Legislative Law.

In the midst of her teaching and legal work, Cook organized for suffrage. As early as 1889, she edited a suffrage column for her hometown newspaper in Indiana. By 1910, she was traveling with a group of fellow Massachusetts Equal Suffrage League members, stopping in a variety of towns over the course of the summer to educate Massachusetts women about citizenship and suffrage rights. She was also a member of the Boston Equal Suffrage Association for Good Government, directing its nominating committee in 1916, and was involved in the Massachusetts Civic League and the State Federation of Women’s Clubs. Cook was vocal about her suffrage views, speaking at club meetings and at the Massachusetts State House, and often writing for the Boston Globe. When the newspaper ran a series of articles in 1909 addressing the question “Why do so few women avail themselves of the school suffrage?” Cook responded with a condemnation of Boston’s voting policies, arguing that the city’s failure to maintain updated lists of women voters made it difficult for women to exercise their right to vote (only in school committee elections) without being forced to register again. Her own name had been purged from voter lists more than once, she wrote, but “my...hardest struggle comes on election day. I cannot get used to the humiliation of being restricted to a small fraction of the ballot privilege which I claim as an intelligent citizen of a country which calls itself a republic.”

Cook’s commitment to equality informed her work as a lawyer, inspiring her advocacy for women’s divorce rights, small loan justice, and a state amendment allowing women attorneys to become notaries. She was Chief Inspector of the Incorporated Charities of the Massachusetts Department of Public Welfare for many years, and in 1913 she helped draft the first minimum wage law in Massachusetts. Cook also served as President of the Industrial Credit Union of Boston in 1910 and head of the Women’s Educational and Industrial Union’s Department of Law and Thrift in 1912. In the 1920s, she became the first president of the Massachusetts Association of Women Lawyers.

Cook died in Boston in August of 1947 and is buried in Evansville, Indiana.

Cook began her teaching career while still in law school, teaching Latin at the Dana Hall School in Wellesley between 1891 and 1899. After passing her bar examinations, Cook went into private practice, maintaining a law office on Beacon Street in Boston, but she never entirely gave up teaching. She taught courses in Business Methods and Commercial Law at Simmons in 1907 and again from 1910-1913, and also returned intermittently to Wellesley during this time as an instructor in Legislative Law.

In the midst of her teaching and legal work, Cook organized for suffrage. As early as 1889, she edited a suffrage column for her hometown newspaper in Indiana. By 1910, she was traveling with a group of fellow Massachusetts Equal Suffrage League members, stopping in a variety of towns over the course of the summer to educate Massachusetts women about citizenship and suffrage rights. She was also a member of the Boston Equal Suffrage Association for Good Government, directing its nominating committee in 1916, and was involved in the Massachusetts Civic League and the State Federation of Women’s Clubs. Cook was vocal about her suffrage views, speaking at club meetings and at the Massachusetts State House, and often writing for the Boston Globe. When the newspaper ran a series of articles in 1909 addressing the question “Why do so few women avail themselves of the school suffrage?” Cook responded with a condemnation of Boston’s voting policies, arguing that the city’s failure to maintain updated lists of women voters made it difficult for women to exercise their right to vote (only in school committee elections) without being forced to register again. Her own name had been purged from voter lists more than once, she wrote, but “my...hardest struggle comes on election day. I cannot get used to the humiliation of being restricted to a small fraction of the ballot privilege which I claim as an intelligent citizen of a country which calls itself a republic.”

Cook’s commitment to equality informed her work as a lawyer, inspiring her advocacy for women’s divorce rights, small loan justice, and a state amendment allowing women attorneys to become notaries. She was Chief Inspector of the Incorporated Charities of the Massachusetts Department of Public Welfare for many years, and in 1913 she helped draft the first minimum wage law in Massachusetts. Cook also served as President of the Industrial Credit Union of Boston in 1910 and head of the Women’s Educational and Industrial Union’s Department of Law and Thrift in 1912. In the 1920s, she became the first president of the Massachusetts Association of Women Lawyers.

Cook died in Boston in August of 1947 and is buried in Evansville, Indiana.

Creator

The Wellesley College Legenda

Source

The Wellesley College Legenda

Date

1884

Citation

The Wellesley College Legenda, “Caroline J. Cook

Faculty, Business and Law,” Suffrage at Simmons, accessed March 9, 2026, https://beatleyweb.simmons.edu/suffrage/items/show/85.

Faculty, Business and Law,” Suffrage at Simmons, accessed March 9, 2026, https://beatleyweb.simmons.edu/suffrage/items/show/85.