Marching in Protest

The 1914 Boston Suffrage March

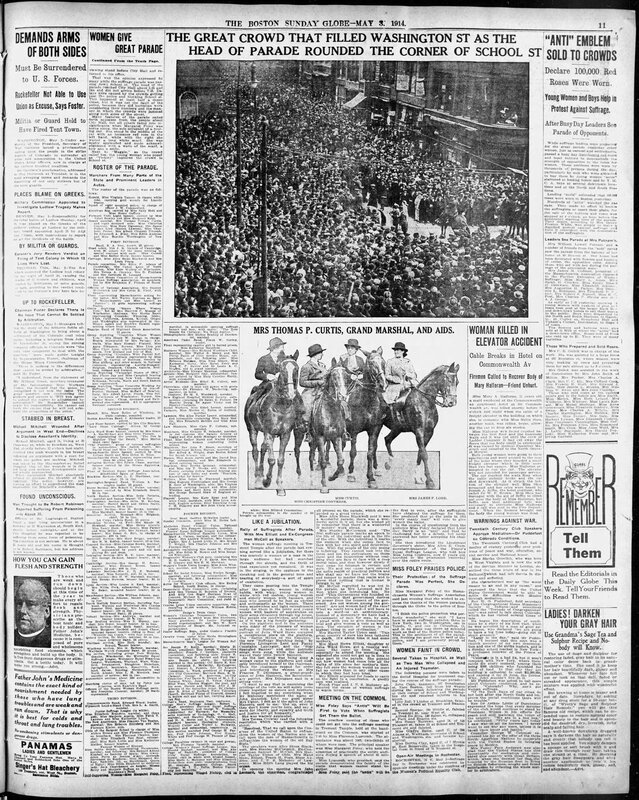

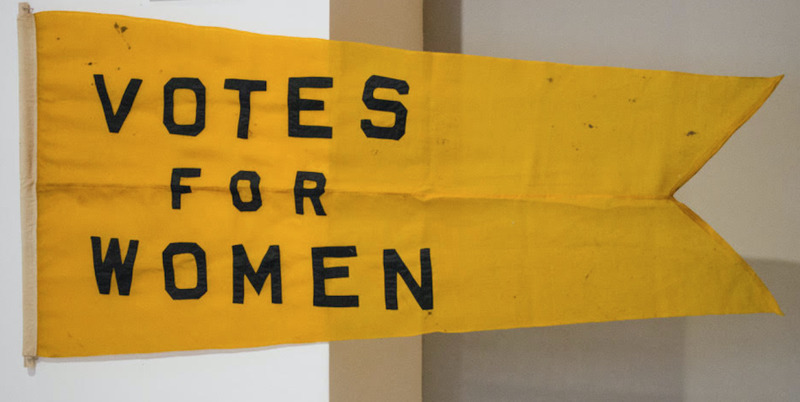

On May 2nd, 1914, Simmons student Gladys Corthell joined a historic march: the first suffrage parade that had ever been held in Massachusetts. Gladys, being from Wyoming, had a particularly unique view on Boston-based suffrage demonstrations; Wyoming women had been voting since 1870. As Gladys wrote in a letter to her mother, over 7,000 people had pledged to march, but between 12,000 and 15,000 showed up that day. The Boston Globe’s headline described, “The Great Crowd that Filled Washington St,” and estimates now agree that alongside the 12,000-15,000 marchers were an additional 200,000-300,000 spectators.

“We walked almost 5 miles, and the sidewalks were simply packed every step of the way. Not only the sidewalk, but the trees, buildings, fire-escapes-- every available spot was full.”

-Gladys Corthell describing the 1914 march

In The Boston Sunday Globe’s coverage of the event, students representing Simmons College marched alongside famous suffragists such as Alice Stone Blackwell, Blanche Ames, and Katherine McCormick, as well as well-known suffrage groups like the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, Massachusetts Men’s League for Woman Suffrage, and the College Equal Suffrage League. The procession passed the State House on Beacon Hill, then marched by City Hall, looped around the business district, and finally returned to hold closing remarks at Tremont Temple.

The 1915 Boston Suffrage Victory March

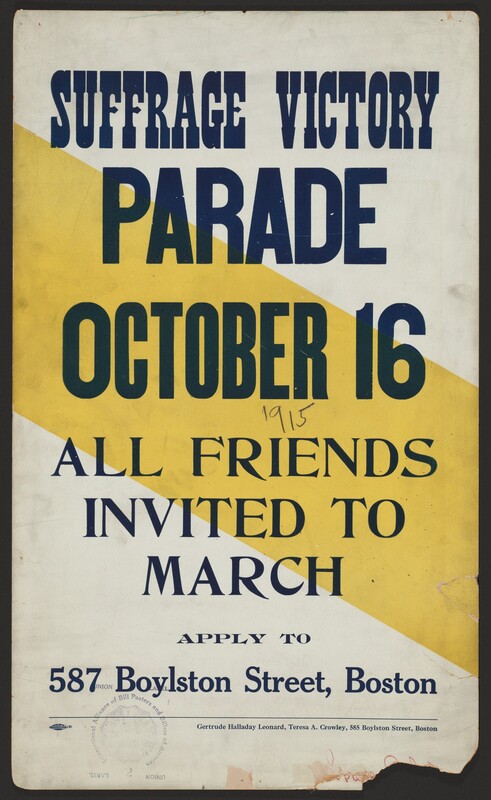

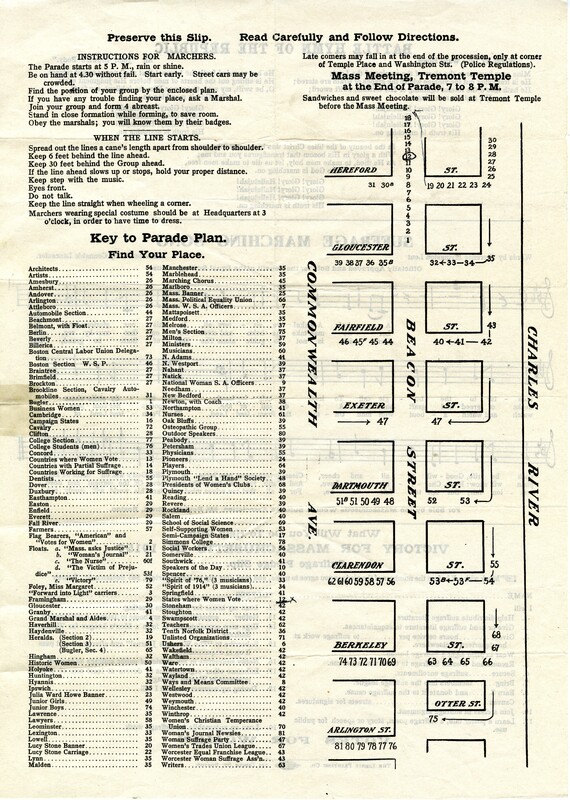

The first Boston march was so successful in garnering support for suffrage that another parade was held on October 16, 1915. This parade hoped to rally support behind a state referendum scheduled for November 2, which had the power to give Massachusetts women the vote if passed. The march included some 15,000 marchers and 30 bands, and the parade began at the corner of Massachusetts Avenue and Beacon Street. It processed by the Public Garden, the Boston Common, and the State House before following Tremont Street and Saint James Avenue to Huntington. Simmons was the only college listed individually on the instructions and map for marchers. The parade ended with a pro-suffrage rally at Mechanics Hall. Even Helen Keller was in attendance at the 1915 march!

The suffrage march made the cover of the Boston Sunday Globe on October 17, 1915 (Courtesy of the Boston Globe)

Once again, Simmons students showed up for suffrage and were noted for their participation by The Boston Sunday Globe’s coverage of the march. However, not everyone in Boston was as enthusiastic about suffrage as the marchers. Anti-suffragists (“antis”) made themselves particularly visible that day. On the day of the parade, the "antis" prepared over 100,000 red "blushing" roses for protestors to wear in silent testimony to their opposition to women's suffrage.

Pro-suffrage marchers processed past houses draped with red banners bearing anti-suffrage slogans and motor cars festooned with giant red paper flowers, "hover[ed]...like flying cavalry seeking an opening for a flank attack" as boys ran among the crowd of spectators selling red roses pinned to cards bearing anti-suffrage messages.”

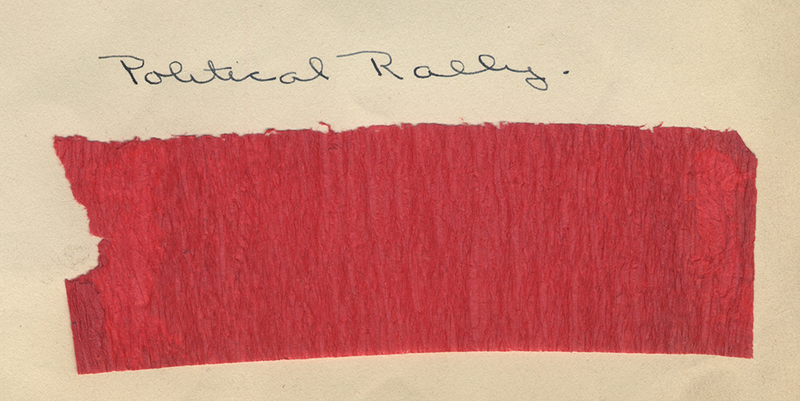

Blanche Castleman: Pro or Anti?

Blanche Castleman, a Library student in the class of 1919, attended this October march. Blanche might have attended merely as a spectator, as her exact views on suffrage are not known. But she kept a piece of streamer from the march in her scrapbook, identifying it only as from a “political rally.” The color of the streamer could be a clue to what she really thought about the monumental question of women’s voting rights. It was red, the identifying color for anti-suffragists.

Ultimately, Massachusetts did not pass the ballot measure that would give women suffrage in 1915, and Massachusetts women did not get the vote until the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920. However, this setback did not stop suffrage organizing in Massachusetts. Instead, it lit a fire within Massachusetts suffragists, who continued to fight for the right to vote until the state ratified the 19th Amendment.