College Women for the Vote

Coming of age with the suffrage movement

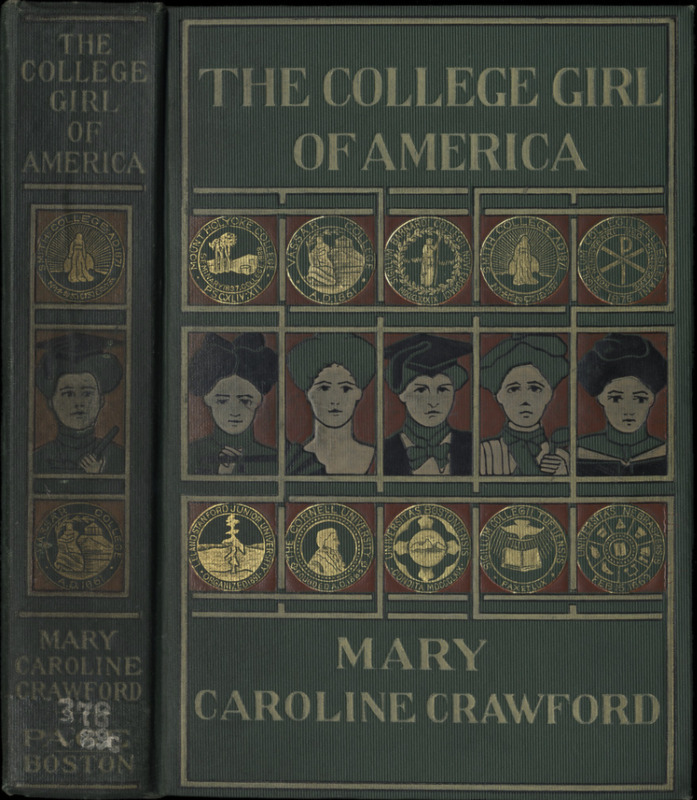

Mary Caroline Crawford's The College Girl of America and the Institutions Which Make Her What She Is (1905)

College women’s organized activism for the vote emerged at the same time and place -- turn of the twentieth century Boston -- of Simmons College’s founding. Simmons’s organization as a college drew inspiration mainly from the Massachusetts Institution of Technology and the Women’s Industrial and Educational Union (WEIU), a non-profit agency created “to increase fellowship among women and to promote the best practical methods for securing their educational, industrial, and social advancement." The WEIU’s president, Mary Morton Kehew, influenced the direction of the college through her position on the Simmons Corporation. Kehew’s fellow suffragists, Frances Baker Ames and Sarah Louise Arnold, served with her on the Committee on Organization at the time Simmons opened in 1901. As Mary Caroline Crawford later wrote in The College Girl in America, Simmons “successfully coalesced the academic and the technical… to give a girl in four years the essentials of a liberal education as well as professional training.” In this way, Simmons opened “lines along which women have heretofore had little or no opportunity to study”: pioneering fields including household economics, library science, social work, and science.

Early student life at Simmons

An image of Martha Washington, a popular icon among suffragists, adorned with a red-white-and-blue bow, from Daisy Miller Helyar's scrapbook

Students in Simmons’s first decades in many ways resembled women at contemporary American universities. They were predominantly white, though they tended to be middle class rather than elite as at many other women’s colleges. The strong partnership with the WEIU reinforced Simmons’s emphasis on practical education, and a substantial percentage of students came to Simmons for post-baccalaureate studies in its early years. Students enjoyed a rich array of extracurricular pursuits, from athletics to student government, from music to a college chapter of the Young Women’s Christian Association (founded in 1912). The vibrancy of campus life shines through the scrapbooks that students kept. A number of developing college traditions, like the Olde English Dinner and the Freshman Junior Wedding, involved costumes and even cross-dressing, which may have encouraged students to think about gender roles and expectations. Even so, as at other universities across the nation, only a minority of the Simmons community embraced suffragism.

Young Radcliffe graduates Maud Wood Park and Inez Haynes Irwin believed that suffrage had special appeal and importance to college women like themselves. From its origins in the nineteenth century, the women’s rights movement had called for education, access to the professions, and economic independence from men; yet the women who benefitted from greater access to those very things seemed indifferent or even opposed to political equality. Park explained in a speech to the NAWSA that she wanted college women to “realize their debt to the women who have worked so hard for us, and to make them understand that one of the ways to pay that debt is to fight the battle in the quarter of the field in which it is still unwon...”

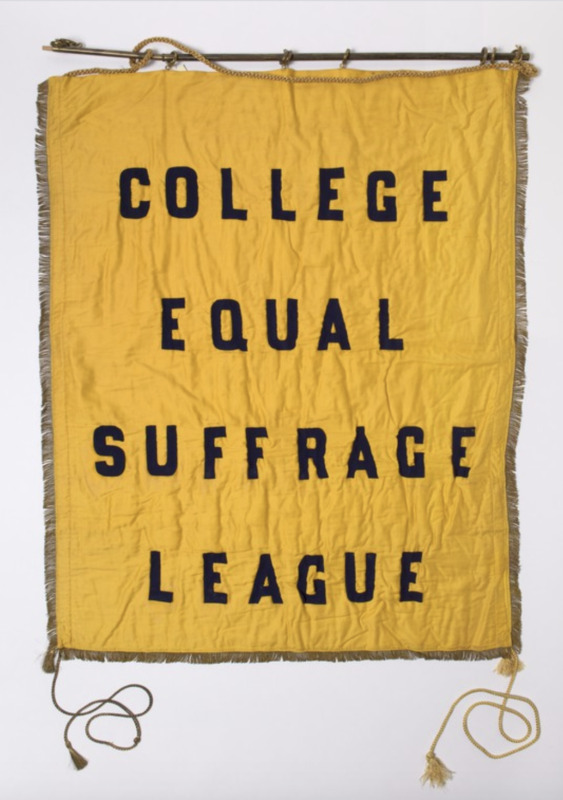

The College Equal Suffrage League

Park and Irwin founded the College Equal Suffrage League (CESL) in 1900 to reach out to students and alumnae, enrich their understanding of democracy and civil rights, and bring younger women into the suffrage movement. At that time, about 2.8% of American women aged 18-21 attended college, comprising about 36% of all college students. They were thus, like college men, a small percentage of the population, but growing in numbers. In 1908, the CESL’s growing number of chapters reorganized as the National College Equal Suffrage League and became a branch of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Simmons postbaccalaureate student Harriet Darling and psychology professor Ethel Puffer Howes both belonged to the CESL. The national organization had 5000 members across the country, including especially active networks in Massachusetts and California.

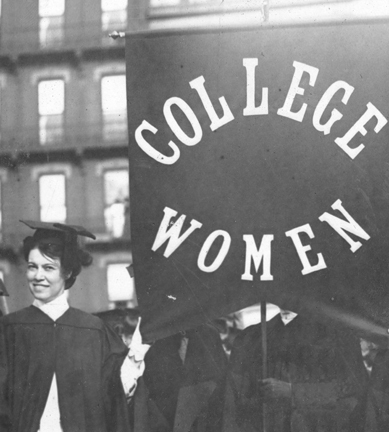

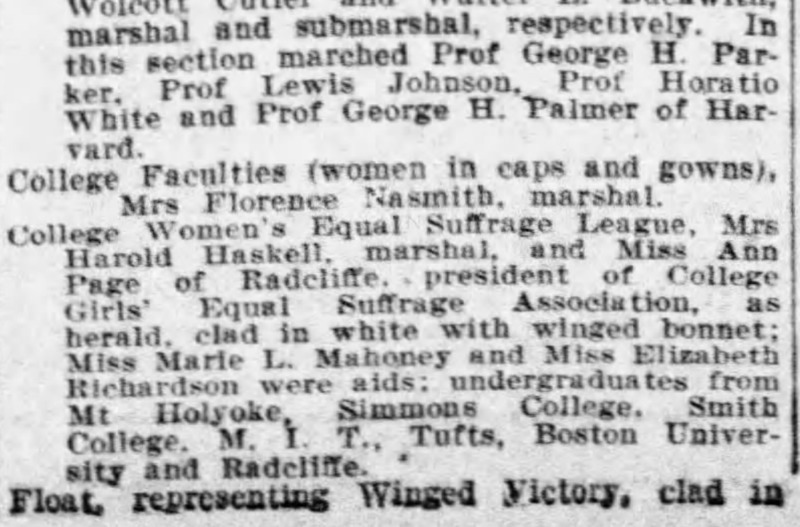

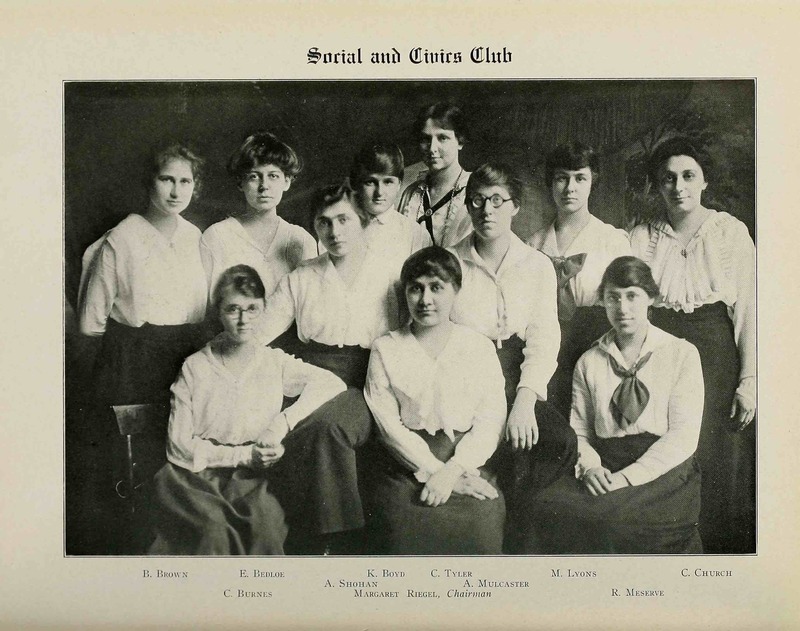

There was no College Equal Suffrage League chapter at Simmons as other colleges, especially women’s colleges. But Simmons students marched with the CESL in Boston’s 1914 suffrage parade. And a Simmons student organization, the Social and Civics Club, hosted the same types of debates, speakers, and other campus activities that the CESL and its chapters sponsored at other colleges.

Unlike other women’s colleges, like Bryn Mawr and Wellesley, where the college president supported suffrage, the anti-suffrage position of Henry Lefavour may have discouraged the formation of a CESL chapter. Or the Simmons community may have preferred engaging in suffragism through the multitude of organizations at their doorstep, in the city of Boston.