Still Waiting for Liberty: 1920-2020

How Long Must Women Wait?

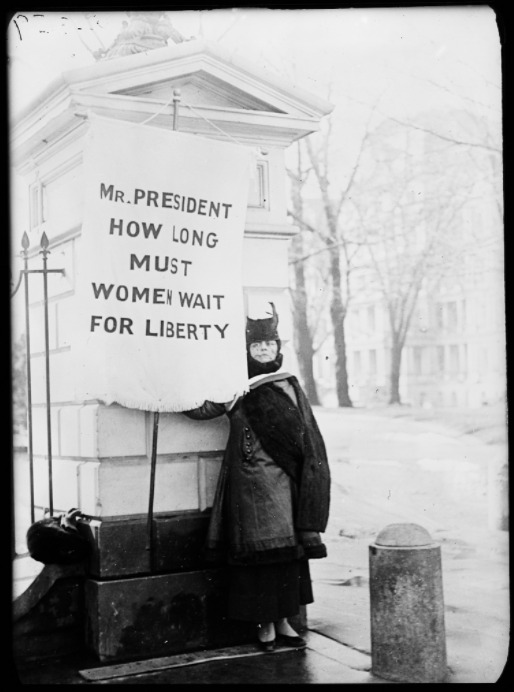

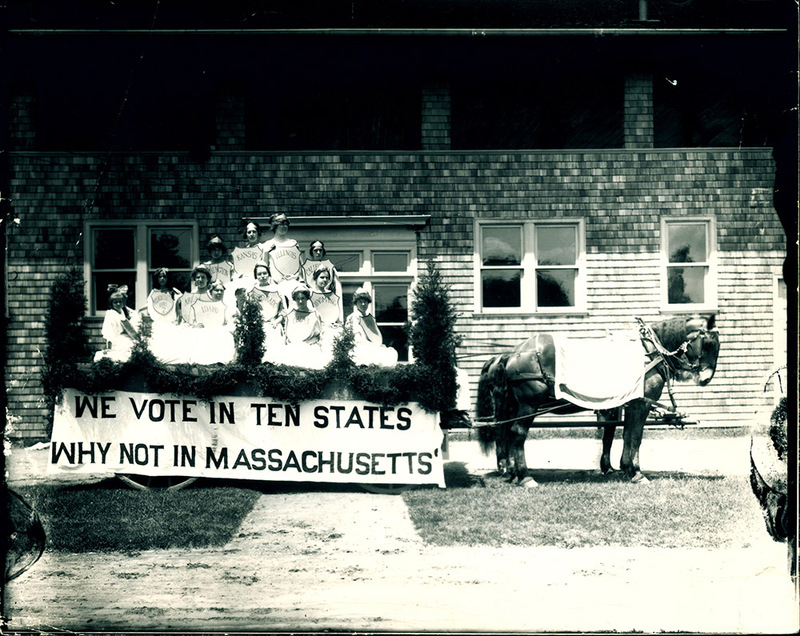

Despite the optimistically named Victory Parade of 1915, with its 15,000 marchers, Massachusetts men voted overwhelmingly against women’s suffrage in the state referendum on November 2. Reckoning with simultaneous defeats in three other states (New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania), the movement reset its focus to the national stage and a Constitutional amendment. The newly formed National Woman’s Party pursued increasingly confrontational tactics, such as picketing the White House, bearing banners that asked “How long must women wait for liberty?” In Boston, suffragists were arrested and jailed after mounting a public protest on Boston Common in February of 1919.

That June, Congress finally passed a women’s suffrage amendment -- over forty years after such an amendment was first introduced. On 29 June 1919, Massachusetts became the 8th state to ratify it.

It took over a year longer for the Amendment to win ratification of the requisite total of 36 states.

The voting rights struggle continues

Although the Nineteenth Amendment became official on August 26, 1920, it did not enfranchise all American women. Women who had emigrated from China, women in “unorganized territories” like Puerto Rico and the Philippines, women who married foreigners, and many Native American women were not eligible for U.S. citizenship. Not being citizens, they could not vote, for years or decades after 1920. In addition, Southern states disenfranchised Black women, as they already had disenfranchised Black men, through legal pretexts like literacy tests and poll taxes, as well as through direct voter intimidation and suppression.

In this sense, women’s struggle for the vote continued long after the Nineteenth Amendment. Among the activists who took the lead in subsequent decades were physician Dorothy Boulding Ferebee, of the Simmons class of 1920. Ferebee led civil rights work through organizations including the National Council of Negro Women and the League of Women Voters.

Generations of Black students spoke out on campus about racial prejudice, democracy, and the urgent need for social change. The first Black woman to serve as President of the Student Government Association was Peggy Gray, elected in 1955.

Melnea Cass, known as the “First Lady of Roxbury,” helped to organize Black women in Boston to register to vote in 1920, founded the non-profit social action organization Freedom House in 1949, and later served as President of Boston’s NAACP chapter. Simmons awarded her an honorary doctorate in 1971.The Notable Women of Boston mural at Simmons depicts Cass along with trustee Mary Morton Kehew and other local suffragists, Lucy Stone and Helen Keller.

The Nineteenth's legacy

As we mark the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, we honor the persistent commitment of the Simmons community to achieving equal rights, participatory democracy, and social justice -- the unfinished business of the suffrage movement, whose legacy continues in activism today.