Sarah Louise Arnold: The Suffragist Dean

Sarah Louise Arnold (1859-1943) the beloved first dean of Simmons College, worked very closely with the college president, Henry Levafour, to build the foundations of the school. They seem to have had a harmonious professional relationship throughout Arnold’s two decades at Simmons. But the two were on decidedly opposite sides of the suffrage debate. President Lefavour opposed extending equal voting rights to women. Dean Arnold not only favored women’s suffrage but actively worked towards it. She served in prominent positions in multiple suffrage organizations and lectured publicly on the matter -- all the while keeping her activism carefully off campus.

Blazing trails

Arnold is remembered primarily for her multifaceted career as a pioneer home economist, a leading college administrator, a respected textbook author, and a cherished teacher. Decades before passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, she supervised the primary school system in Minnesota and the Boston public schools. She remained interested in public education long after she left that position to become Dean of Simmons College. She continued to publish on English composition and reading, such as the series See and Say, The Mastery of Words, and The Mother Tongue, along with articles in the Journal of Education.

Making her mark on Simmons

As a member of the Simmons Corporation, Arnold advocated that the new college adopt the New England School of Housekeeping, an experimental educational program created by the Women’s Educational and Industrial Union (WEIU). When Simmons College opened, this became the School of Household Economics, with Dean Arnold as its Director. Its curriculum combined technical practice with academic instruction. Arnold advocated the value of “equipping” women to earn “a livelihood” of their own. Her individual teaching style combined the vocational, the intellectual, and the moral in every lesson:

"Once a week Miss Arnold talks to the students about whatever is newest and most arresting in present-day thought concerning the household. The apostles of the ‘freedom’ of women are then discussed, and the girls are shown that to be free in the highest sense means to be free to serve. The spiritual value of household service is also considered; perhaps Lowell’s ‘She hath no scorn of common things’ is quoted to help make the point at issue. Simmons finds it by no means impossible to unite the scientific and the spiritual."

- Mary Caroline Crawford, The College Girl of America

The lyrics Arnold wrote to the college anthem (1904) emphasized loyalty, labor, and worthiness of trust. And Arnold certainly lived by her ideal of service. As Dean she “was Alma Mater, in the literal meaning of foster mother, to hundreds of girls,” wrote Chemistry professor Kenneth Mark. Arnold went on leave from Simmons to conduct volunteer relief work during World War I, at Governor Alvin T. Fuller’s request. Building on her national reputation in the field of Home Economics -- including serving as president of the American Home Economics Association -- she lectured nationwide for Food Conservation efforts. After completing twenty years as the first Dean of Simmons College, she served as National President of the Girl Scouts of America. Later still, Arnold became the first woman trustee of Massachusetts Agricultural College (1926-1931).

Working for equal suffrage

The extensive public speaking Arnold did during World War I followed over a decade of public speaking for women’s suffrage. Regarding women’s freedom as “a freedom to serve” did not preclude fighting for the equal right to vote. Indeed, Arnold’s experiences as an educational leader may have awakened her consciousness of political inequalities. By 1894, when Arnold returned to Massachusetts as supervisor of the Boston Public Schools, Massachusetts women could vote -- but only in School Committee elections. Few Boston women actually went to the polls merely to vote for the School Committee. Yet “school suffrage” remained the only kind of suffrage women in Massachusetts had until 1920. Though the state considered extending municipal level suffrage to women multiple times, it never passed.

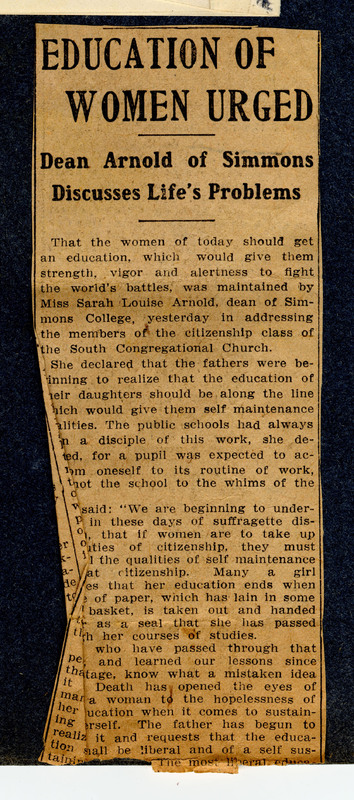

Arnold was active in multiple suffrage organizations around Boston, including both the Boston Equal Suffrage Association for Good Government and the less radical Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association. Her suffrage activism was prominent enough to merit repeated notice by the Boston Globe and other newspapers. Along with work for BESAGG’s department of Moral Education, Arnold also created a Citizenship Education committee within MWSA to teach women about the structure of government in anticipation of gaining the right to vote. She may have discussed these initiatives with students; Daisie Miller Helyar, of the class of 1910, clipped and saved an article about a local suffrage speech by Arnold.

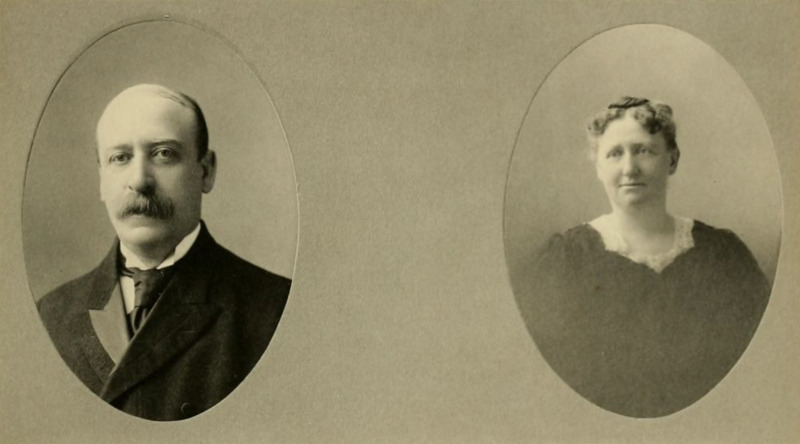

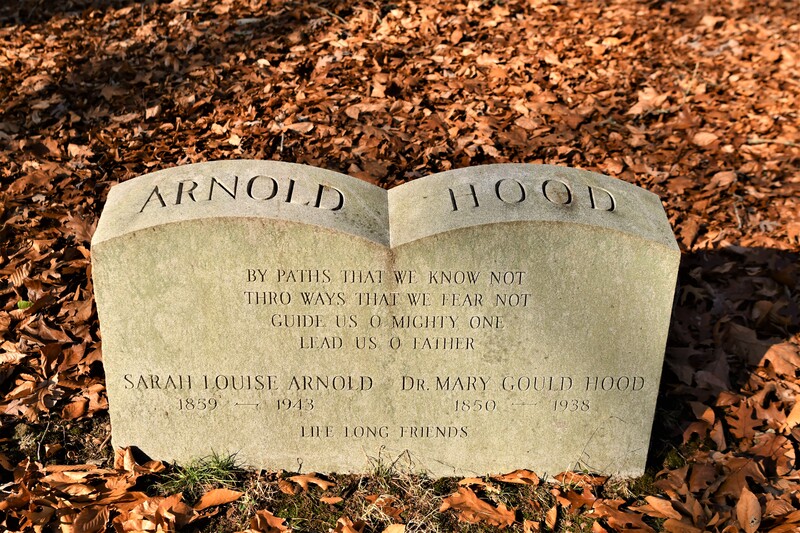

Arnold’s interest in women’s rights and equality extended beyond the right to vote as well. In 1914, she wrote the introduction to one of Dr. Mary Gould Hood’s books, For Girls and the Mothers of Girls, about the necessity of sex education. Hood and Arnold shared a home from 1895 until Hood’s death in 1938. Robert Grose, Arnold’s grandnephew, noted the two women’s close and mutually supportive partnership. Hood had an illustrious career as a physician and helped open the profession of medicine to women.

Her final suffrage speech may have been in 1920 at painter Sarah Eddy’s studio in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, celebrating the passage of the 19th Amendment, at long last.

Honoring beloved Dean Arnold

In 1931, the first graduating class of Simmons honored their suffragist dean with a lavish celebration of their own. They presented the college with a donation of Arnold’s portrait. The painting eventually graced Arnold Hall, a student dormitory named in her honor, which opened in 1951.